By Steven Jakobovic

Sixty years ago, The Central Virginian published W.H. Boyle’s rebuke of a Richmond Times-Dispatch article that described turn-of-the-century Mineral as a “swashbuckling mining town worthy of the Old West…with more saloons than churches.” Mr. Boyle, a retired superintendent from the sulfur mines, respectfully disagreed stating, it “does not jibe with accumulated old-time data which I have.”

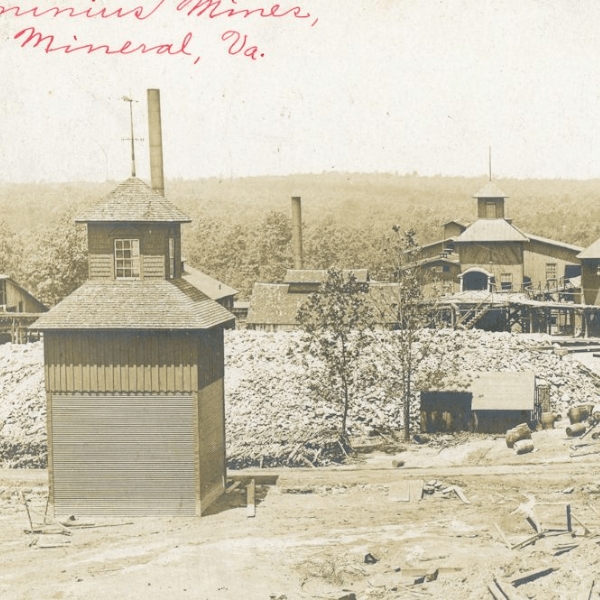

Mr. Boyle pointed to Mineral’s two hotels, “modern school”, bank, and “brilliant mining engineers” who applied their technical knowledge to the region’s excavation efforts. Indeed, the earth in and around Mineral was rich with iron, copper, pyrite, gold and more. As the mining business boomed, so did Mineral – growing from a single house in 1889, when the town was known as Tolersville, to a region that accommodated sulfur mines that at its peak employed well over a thousand workers!

Mining is without a doubt hard work. In Mineral, not only did miners work underground, but workers transporting ore on skips (see picture) couldn’t be afraid of heights either. Although they looked pretty rickety, early twentieth century skips could transport three to four tons of ore at a time to nearby crushers for processing. If a person had or was willing to develop a skill, jobs at the mines were many and varied. They included machinists, pump men, mill workers, mill engineers, blacksmiths, watchmen, firemen, painters, drivers, carpenters, masons, and more.

After a long day of working at the mines, the miners enjoyed a drink, or perhaps one drink too many. It didn’t take long for dozens of entrepreneurs to seize on the opportunity by opening saloons to cater to thirsty workers. The rowdiness of drunk miners became a concern. Albon P. Mann, a manager at the Arminius Mines, complained that the disturbances by the “roughs residing in the neighborhood…have been more than ordinarily frequent.” A shooting that took place in front of Hogg’s Place tavern fueled local prohibitionists in Mineral and Louisa County.

However, as Mr. Boyle noted in his letter to the editor, the presence of mining was clearly beneficial. As mining increased, so did a community around the mines. Episcopal, Baptist and Methodist churches were erected. Flour and grist mills were built. Local railroads scaled up and other businesses were established. An essay by William Kiblinger in the Louisa County Historical Society Magazine notes that there were many activities sponsored by the mines including baseball games. A baseball diamond with bleachers drew large crowds to watch games between the Crenshaw and Arminius mining companies.

In all likelihood, most miners simply left work to go home to their families. Many miners were provided with company-built housing (see picture).

Photographs also suggest that family members worked beside each other. Boyd Brooks, Johnnie Brooks and D. Brooks, pictured at the top of this post, were probably brothers that worked together in the sulfur mines (notice that the two men standing behind Boyd Brooks were holding puppies – clearly miners had a soft side).

As the prohibitionists continued their efforts to quiet down the “roughs” in Mineral, culminating with a successful Virginia-wide vote to become a dry state in 1916, little did they know how quiet the town would soon become. By the early 1920s, the last commercial mines closed in Mineral. The hard pyrite ore found in Mineral required operations that were inefficient when compared to mines in other parts of the country. While many families left Mineral for work elsewhere, Johnnie A. Brooks, likely the same Johnnie pictured above, lived in the area until the ripe age of eighty as documented by The Central Virginian.

W.H. Boyle had fond memories of Mineral. You might say he thought that the richness under the ground led to a rich historical legacy above the ground.

The Louisa County Historical Society invites you to stop by the Sargeant Museum where items from Mineral’s mining boom are on display.