By Janice Lorenz and Brianna Patten

Driving into Bracketts Farm on the gravel road, it almost feels like you’re traveling back in time. There are pastures with grazing cattle, rolling hills, gardens, and minimally altered historic buildings. I had to stop myself from daydreaming about what life was like here centuries ago when I almost walked into someone’s house. I missed the sign that said “Private Residence” on the front porch of an old farmhouse. A few people are lucky enough to still live on this 500-acre property in a National Park historic landmark district.

Photos by Bracketts Farm

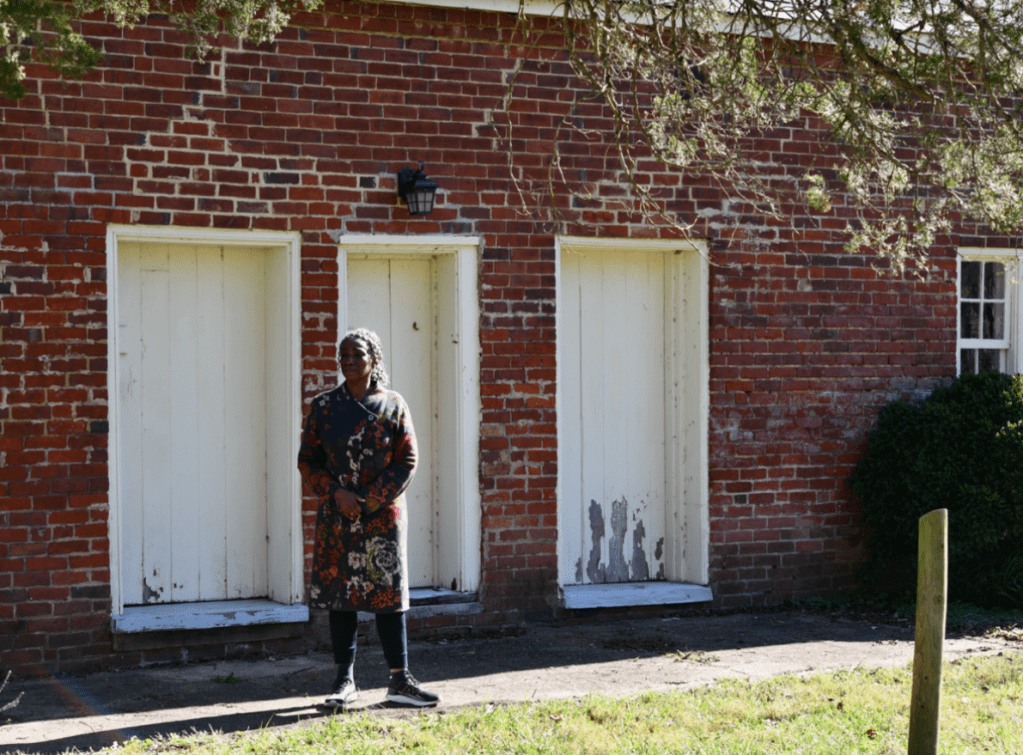

Right next to the houses people are still living in, there’s a brick building with three white doors where some of the enslaved people at Bracketts once stayed. For Janice Lorenz and a growing community of descendants of enslaved African-Americans, this land is a sacred place their ancestors once called home.

Janice standing outside of the enslaved people’s quarters at Bracketts Farm. Since at one point there were almost 50 enslaved workers at Bracketts, there were likely other less permanent structures throughout the property where enslaved workers lived.

Janice has spent years doing genealogical research and recording her family tree. Throughout her arduous (but rewarding) research process, folks at the Louisa County Historical Society have been by her side with resources and support. I was honored to meet Janice in these enslaved people’s quarters at Bracketts Farm where her ancestors once lived and worked. We had an enlightening conversation about her genealogical research and the incredible achievements of her family throughout history. The following is an abridged transcription of our conversation. We hope you learn something about the remarkable lives of African-Americans in Louisa County and leave inspired to research and record your own family history.

Janice looking out the window of the enslaved people’s quarters at Bracketts Farm

What inspired you to start researching your genealogy?

Looking back, it was the oral histories I was given and the opportunities I had to travel with my parents as a young person. Getting to learn about my father’s family [the Rosses], who were enslaved people who settled in Kansas. I have some pictures of me with my father in Kansas; I couldn’t have been any more than two or three years old. Also, a great-aunt on my father’s side [Eliza Ross] came to live with us in Washington, D.C. She brought a lot of documents and heirlooms with her. Later in life, I realized I had a treasure trove of information about my family out in Kansas. These items told of their enslavement, service in the Civil War, post-war homesteading, and their legacy of five well-educated children.

My mother, Marjorie Quarles, also spoke about her Aunt Grace, who was a Quarles and lived in Louisa County and then Culpeper. I didn’t really pay a whole lot of attention to that side of the family until she said to me, “You know, your great-grandfather [James Kelly] is buried in Arlington Cemetery. He was a Civil War veteran.”

I have one picture of my great-grandmother Margaret Minor who was enslaved in this area and I was astounded to learn that she did, in fact have a family here. She was Watson and a Minor as a result of her parents working in this area as enslaved people. So based on those oral histories as well as documentation that I had, that really kind of got me going. Now that I’m retired I have the time to really do a lot of digging with my husband John.

Janice with her father and Great Aunt Eliza Ross in Olathe, Kansas (1951). Eliza was the last surviving child of Margaret Chapman Ross and Civil War veteran James Whitfield Ross

What was it like when you found out that your ancestors were enslaved at Bracketts? What did it feel like visiting this property for the first time?

At first, I was a little confused because I didn’t get true documentation that my Minor, Quarles, and Watson families were actually on this plantation until very recently. But still, when I walked through the door here, and just to be in the presence of a structure that was inhabited by enslaved people, I kind of stepped over the threshold and then stepped back. I had this almost spiritual experience. I felt a sense that these people, my ancestors, walked through these rooms and lived here.

I know that my ancestors were also at the Hawkwood Plantation. There was a sharing of enslaved people at Hawkwood who came to work here at Bracketts. They were doing hard work here. We still need to do more research as to who these folks were, when they came and worked on this farm, and what their connection was to the families here.*

How did the Louisa County Historical Society help you throughout your research process?

A few years back, I found the Louisa County Historical Society and attended a genealogical workshop. There were several people there. One was Gloria Gilmore, who was on the board. Gloria said to me, “You know, you really ought to do your family tree.” And when I mentioned the family surname of Minor, she said, “Oh! I’m a Minor too!” That really established a personal relationship between us through emails. She shared with me information about the Minors, the Watsons, and the Quarles, all of whom again were in this location at some point in their lives, both as enslaved people and as Free People.

The Historical Society has published several books, one of which is Old Home Places, and in it, the Quarles, Watsons, and Minors are mentioned. That opened the door to all of these sights here in the Green Springs area and gave us some clues to where family members might have lived. If there’s anyone who’s interested in their family connections to Louisa County, this book is well worth buying.

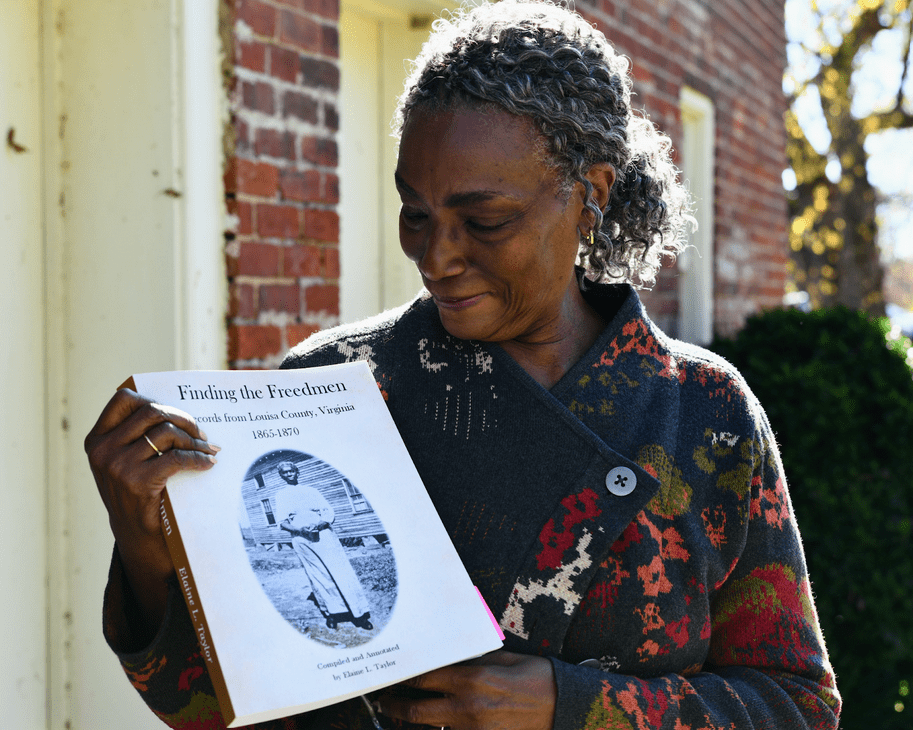

The Historical Society has also digitized some historical data called “Piedmont Virginia Digital Histories: The Land Between the Rivers,” which is free online. That was really quite helpful. As a result of that particular website, we found records of marriages and voting lists. Believe it or not, my great-grandfather Armistead Quarles and great-great grandfather Arthur Quarles voted in 1867. That blew our minds. The fact that we had family members that felt so strongly after gaining their freedom, and as part of the Reconstruction Era, did go out and vote. There is also another book by Elaine Taylor called Finding the Freedmen which contains records from Louisa County’s African-American population from the end of the Civil War to 1870. And on the front of the book is a Quarles who lived and worked here at Bracketts too.

Janice outside of the enslaved people’s quarters at Bracketts Farm holding Finding the Freedmen by Elaine Taylor. On the cover is a photo of Barbara Johnson Tinsley, daughter of Martha Quarles. Barbara worked at Bracketts as a cook, helped operate a country inn, and raised violets that were sold up and down the East Coast.

How does having this knowledge about your ancestors impact how you view yourself and the world?

I think I’ve been influenced by the mystery of it all, finding bits and pieces of information. On both my mother’s and my father’s side, the stories are just incredible. It’s truly an American story. Some of it was horrible, but my family was a part of that story as enslaved people.

There were love stories. In some of the documents that I have on my mother’s side, she had a great-grandfather who told his sweetheart not to mess with anybody when he ran off to join a Black Union Regiment because he’d come back and marry her, and he did marry her! He was wounded in the war, but they started a family together after. I have all of this documented in a pension affidavit.

My great-grandmother Margaret Quarles was part of the Great Migration North. She moved to Philadelphia with her daughter Grace, who had an impact on my mother. [Grace] took care of my mother during the Depression. So from here to Philadelphia, there’s a fascinating story about how my family took care of one another.

Why do you think it’s important for people, specifically Black people, to research their genealogy?

I know it’s hard as people are working. It’s time-consuming, but once you get bitten by the research bug, it will be hard to stop. These stories elevate you to a sense of pride and resilience. I like to think maybe genetically that’s been passed on. You get the causal effect of why we are the way we are, because of the struggle from enslavement to where we are now. These stories are empowering. I think Black people can learn a lot from how an individual can survive and still maintain dignity, maintain a family, and pass on moral principles that continue on today.

What advice do you have for Black folks who are in the process of researching their family history?

Starting with little steps like subscribing to Ancestry.com or connecting with a historical society can help. Certainly, listen to your elders. A lot of times, we don’t sit down with them and ask questions. I was fortunate because I got to travel. We traveled all over and got a sense of other places, a world that’s bigger than Washington, D.C., where I grew up. Just getting a sense of our country, you learn a lot about yourself and your place in the world. Just get on the bus, you don’t even have to fly. Get on the bus and come to Louisa County or Richmond or Philadelphia. You’ll find that the world is bigger than yourself.

Would you like some help researching your family’s history in Louisa County? Fill out a research inquiry and one of our staff or volunteers will be in contact with you.

If you’re ever here in Louisa County, make sure to visit the Sargeant Museum at the Louisa County Historical Society and Bracketts Farm!

*This information comes from an 1862 list of slaves prepared by the owner, E. O. Morris. Four first names without surnames, Armistead, Margaret, Overton, and Louisa correspond to known family members who emerged in post-Civil War documents with their surnames (Quarles, Minor, Minor, and Watson/Minor). We also know from several sources that there was a sharing of slave labor among plantations in Green Springs, including Bracketts. Finally, we know that the African- American surnames Quarles, Watson, and Minor (all in Janice’s family) were present at Bracketts both before and after the Civil War.